How to *define* your *value proposition*?

Every successful startup needs a Unique Value Proposition (UVP) at its core. A UVP is more than a catchy tagline – it’s the fundamental promise of value that you deliver to customers, and it underpins your entire business strategy. A strong UVP guides what you build, how you talk about your product, how you position against competitors, and even how you pitch to investors. In early stages, founders often wear many hats, but one of the most critical tasks is articulating exactly why your product is different and worth paying attention to.

Why focus on UVP?

A well-defined UVP becomes a strategic tool that influences everything: product decisions, messaging and branding, market positioning, fundraising narratives, and internal alignment. Like the unseen foundation of a house, a strong UVP supports everything built on top of it. It clarifies your vision and rallies your team around a common purpose. On the flip side, an unclear or generic value proposition can confuse customers and even raise red flags with investors (a vague, buzzword-filled tagline often signals a lack of clarity in vision). By investing time upfront to nail your UVP, you establish a “north star” for your startup’s growth.

What is a Value Proposition?

In simple terms, a value proposition is a concise statement of the unique benefit your product or service delivers to a specific customer segment. It’s the answer to the customer’s eternal question: “Why should I choose your solution over all the others?” A good UVP is typically a single, clear, and compelling message that communicates:

- what you offer,

- who is it for, and

- why it's better or different than alternatives.

Why does a UVP matter so much?

- Customer Appeal: a well-crafted UVP makes it immediately obvious what problem you solve and why it’s relevant to them. It improves your conversion, retention, and referrals.

- Consistent Branding and Messaging: it keeps your marketing copy, sales pitches, and even investor decks on-message and aligned.

- Internal Alignment: for everything from product development to marketing. Every feature you build and every campaign you launch should ladder up to the value promised in your UVP.

- Investor Confidence: VCs often make snap judgments based on how clearly you can state the problem you solve and the benefit you provide.

What Makes a Good UVP?

Not all value propositions are created equal. Some are unforgettable and compelling, while others fall flat. Here are a few hallmarks of a strong UVP:

- Clear & Simple: It’s straightforward to grasp instantly, even for someone without expertise. Steer clear of jargon and buzzwords; opt for simple, direct language instead. An effective UVP should not leave people confused – it should "click" right away.

- Customer-Centric & Outcome-Focused: A great UVP speaks to the outcome or benefit the customer cares about – not just a list of features. It addresses a concrete problem, need, or desire. In other words, it’s about them, not you. For example, instead of “We use advanced AI algorithms,” an outcome-focused UVP would be “We help you find fraud 5x faster using AI.” Focus on how you improve the customer’s life or business. The product or feature is not the value - it’s how value is delivered.

- Unique & Differentiated: Your value proposition should highlight what sets you apart. If it could just as easily describe your competitor, it’s not unique enough. A good UVP might explicitly or implicitly answer “Why us and not the other guys?” – whether that’s a unique approach, an exclusive resource, superior performance, cost advantage, etc. For instance, “the only budget app built specifically for freelancers” is inherently differentiated. Often, the specificity of your target or outcome can make it unique (e.g. “for busy moms,” “for B2B SaaS marketers,” “save 10 hours/week,” etc.). Don’t be afraid to niche down – a focused UVP for a specific audience is usually stronger than a vague one trying to please everyone.

- Credible & Testable: A strong UVP is one you can back up with evidence – and one you can validate through testing. It’s essentially a hypothesis about what customers value, so it should be framed in a way you can test and refine. For example, if your UVP is “Cut online checkout time in half,” you can measure whether users indeed checkout faster with your product. Being specific (with metrics or concrete claims) not only makes your UVP more credible, but it also gives you something to prove. You’ll want to incorporate proof points – facts, data, or testimonials that support your claims . For instance, if you claim “fastest delivery,” you should have data like “delivered in under 2 hours on average” or a customer quote to back it up. Moreover, treat your UVP as a living hypothesis: put it in front of customers (on a landing page, in a pitch, etc.) and see if it resonates, then iterate.

- Concise & Memorable: The best UVPs don’t try to cram in every detail. They often consist of a tagline or sentence plus maybe a short supporting sub-header or bullets. The idea is to communicate one big thing that sticks. Think of slogans or one-liners that have stuck with you (Just Do It – Nike or Be less busy - Slack).

Next, we’ll dive into some frameworks that can help you formulate your UVP, and then we’ll see real examples and go through a step-by-step process to create your own.

Three Frameworks to Define Your UVP

There is no one-size-fits-all formula for a value proposition, but there are proven frameworks that can guide your thinking. Here we introduce three influential frameworks to help you clarify your UVP from different angles: Jobs to Be Done, Porter’s Value Proposition Triangle, and Strategyzer’s Value Proposition Canvas. Each framework offers a lens for understanding how your product creates value in a unique way.

1. Jobs to Be Done (Clayton Christensen)

Why do customers really buy your product? The Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) framework, popularized by Clay Christensen, helps you answer this by shifting perspective: instead of focusing on customer demographics or product features, look at the underlying “job” the customer is hiring your product to do. In Christensen’s words, "customers don’t simply buy products; they “hire” them to get a job done" . Every purchase has a context and motivation behind it – a problem to solve, a goal to achieve, or a pain to alleviate. JTBD asks: What is the progress the customer is trying to make in their life or business?

Under this framework, you delve into the functional, social, and emotional dimensions of customer needs . For example, the famous “milkshake” example from Christensen’s research showed that people were “hiring” milkshakes in the morning not just for taste, but to relieve boredom on a commute and to have a convenient, tidy breakfast. This insight led to a better product and marketing strategy for milkshakes (e.g. making them thicker so they last longer during a drive, and marketing the morning use-case).

Food for thought:The JTBD mindset would have you fill in the sentence: “When _____ (situation), customers want to _____ (job to be done) so they can _____ (desired outcome).”

How JTBD informs your UVP: Once you identify the core job (or jobs) your product does for the customer, you can craft your UVP around that. It ensures your proposition is outcome-focused (the outcome being the job accomplished) and customer-centric (rooted in the customer’s context). For example, a ride-hailing service’s job-to-be-done might be “get me from A to B quickly and safely.” A UVP for an early ride-hailing startup might then be “Tap a button, get a ride in minutes – the fastest way to get from A to B in the city.” Notice how that speaks to the job (quick, convenient transport) rather than the technology (it doesn’t say “we have an app-based taxi network,” which is feature-focused).

As you develop your UVP, use JTBD to interview customers or observe behavior: ask questions like “What problem were you trying to solve when you used our product?” or “Think of the last time you [context], what did you do and why?” The answers will be gold for phrasing your value in terms that matter to customers (often, you’ll even pick up the exact words customers use – which you can mirror in your messaging).

Key takeaway from JTBD: Frame your value proposition around the job the customer needs done and the outcome they’re seeking, not just around your product’s specs. This ensures your UVP hits the nail on the head in terms of relevance and clarity.

Food for thought:

Customers “hire” products/services to accomplish a “job.”

Your Mission: Identify the job they need done, the pains they face doing it, and the gains or outcomes they aspire to.

Example: A mother “hires” a meal kit delivery service so she can quickly prepare healthy dinners while juggling a busy schedule. She’s not buying “food” but a time-saving, stress-reducing solution.

2. Porter’s Value Proposition Triangle (Michael Porter)

Michael Porter, a renowned strategy professor, describes strategy as defining a unique position, and at the heart of a company’s strategy is its value proposition. Porter suggests that a unique value proposition can be identified by answering three fundamental questions (often depicted as the three points of a triangle):

Porter’s “triangle” model of UVP: strategy is defined by which customers you target, which needs you meet, and at what relative price (or cost).

- Which customers are you going to serve?Within any market, you can segment customers in various ways (by demographics, behavior, size, etc.). A value proposition can be tailored to specific segment(s). Defining who you are focusing on is the first leg of the triangle. For some companies, this is the primary decision: e.g. “We are building for first-time parents,” or “our solution is for freelance graphic designers.” By choosing a distinct target, you automatically shape the other aspects of your strategy. Porter notes that in some strategies, choosing the customer segment comes first, and it guides the needs you will address and the price position you’ll take .

- Which needs (customer problems) are you going to meet? – The second leg is clarifying what key problem, need, or job (to echo JTBD) you will satisfy for the chosen customers. In some strategies, this is the primary focus: you identify an unmet need or a set of needs in the market and build a superior way to meet them. For example, a company might decide, “We will meet the need for affordable on-demand transportation in rural areas” or “We will solve the pain of manual data entry for accountants.” Often, this choice is linked to unique capabilities you have to solve that need. If your UVP is need-driven, it should articulate that unique solution to that pressing customer need.

- What relative price will you offer (and thus, what value/cost trade-off)? – The third leg of Porter’s triangle is your price positioning relative to the alternatives. Are you a high-price, premium value offering? Or a low-cost, “good enough” offering? Some of the most successful value propositions win by changing the price equation. For example, a company may target customers who are overserved and overpaying for existing solutions, and offer a simpler product at a much lower price – capturing those customers with a “good enough” solution at a bargain . Conversely, another company might target customers who are underserved by cheap solutions and are willing to pay more for a premium product that fully meets their needs. Either way, relative price is part of your value proposition: it tells the customer whether you’re a luxury choice, a cost-effective alternative, or mid-range. Importantly, your price must align with the value you deliver and the segment you target (e.g. a cash-strapped small business segment will need a different price/value combo than enterprise clients).

According to Porter, a truly unique value proposition comes from making distinctive choices in these three areas and aligning them. Your UVP essentially boils down to “We serve X customers, fulfilling Y needs, at Z price point (relative to others)”. For example, Ikea’s value proposition can be described via this triangle: Target (X) – cost-conscious young furniture buyers; Needs (Y) – stylish, space-efficient furniture solutions that can be taken home immediately; Relative Price (Z) – significantly lower cost than traditional furniture stores (achieved via flat-pack self-assembly and warehouse stores). All of Ikea’s messaging and strategic decisions align to that UVP (e.g. “Affordable design for the many” is a phrase that captures it).

How to use this framework: Ensure your UVP clearly reflects a choice in who and what – and consider mentioning the element of how/price if it’s a key part of your differentiation. For instance, if your offer is 30% cheaper than competitors for a comparable service, that cost advantage might be front-and-center in your UVP. On the other hand, if you’re premium, your UVP might focus on the superior quality/outcomes and implicitly justify the higher price. The triangle reminds us that being all things to all customers is not a strategy. A strong UVP stakes out a focused position.

Food for thought:

1. Which customers are you going to serve?

2. Which needs are you going to meet?

3. What relative price or quality level?

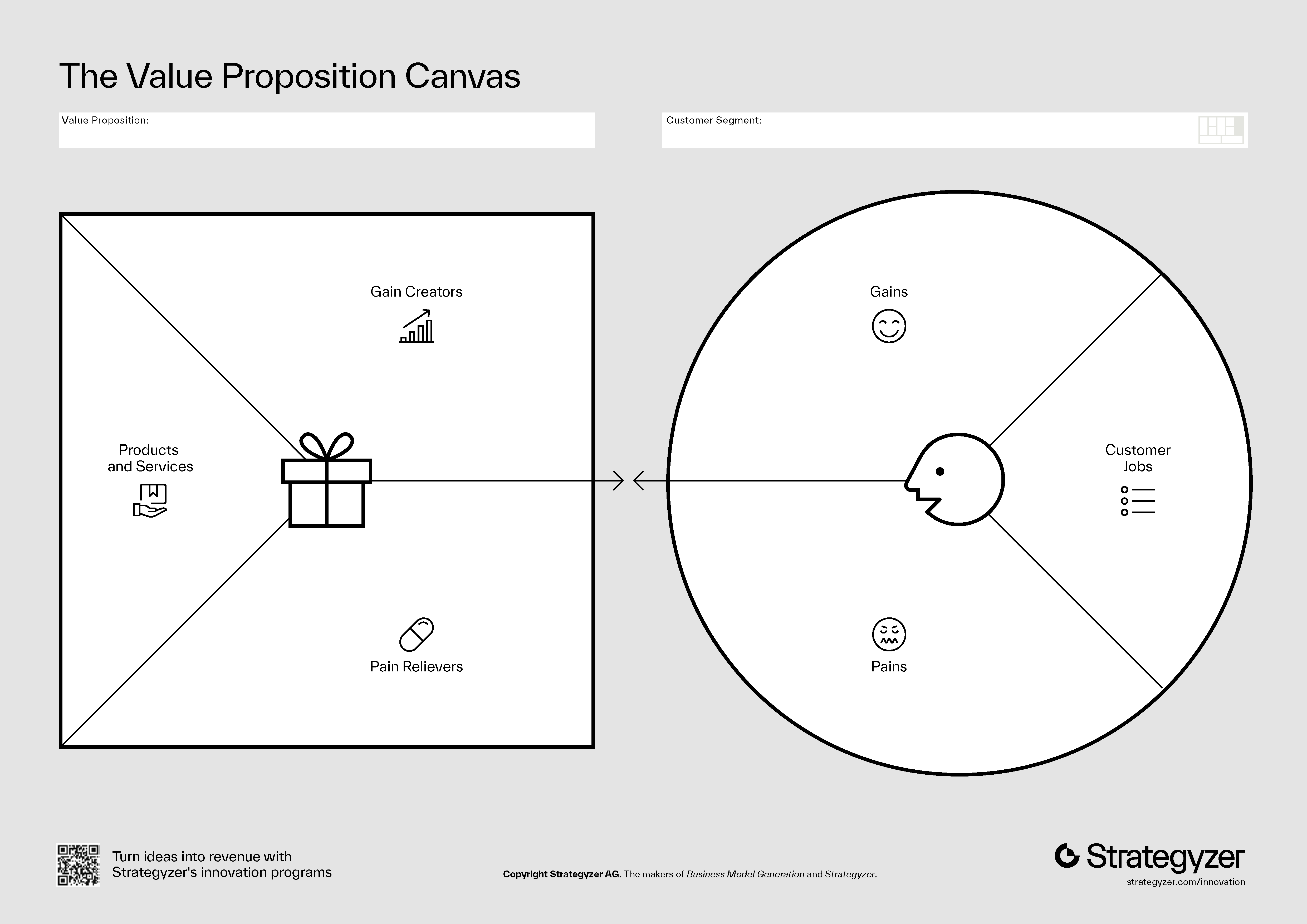

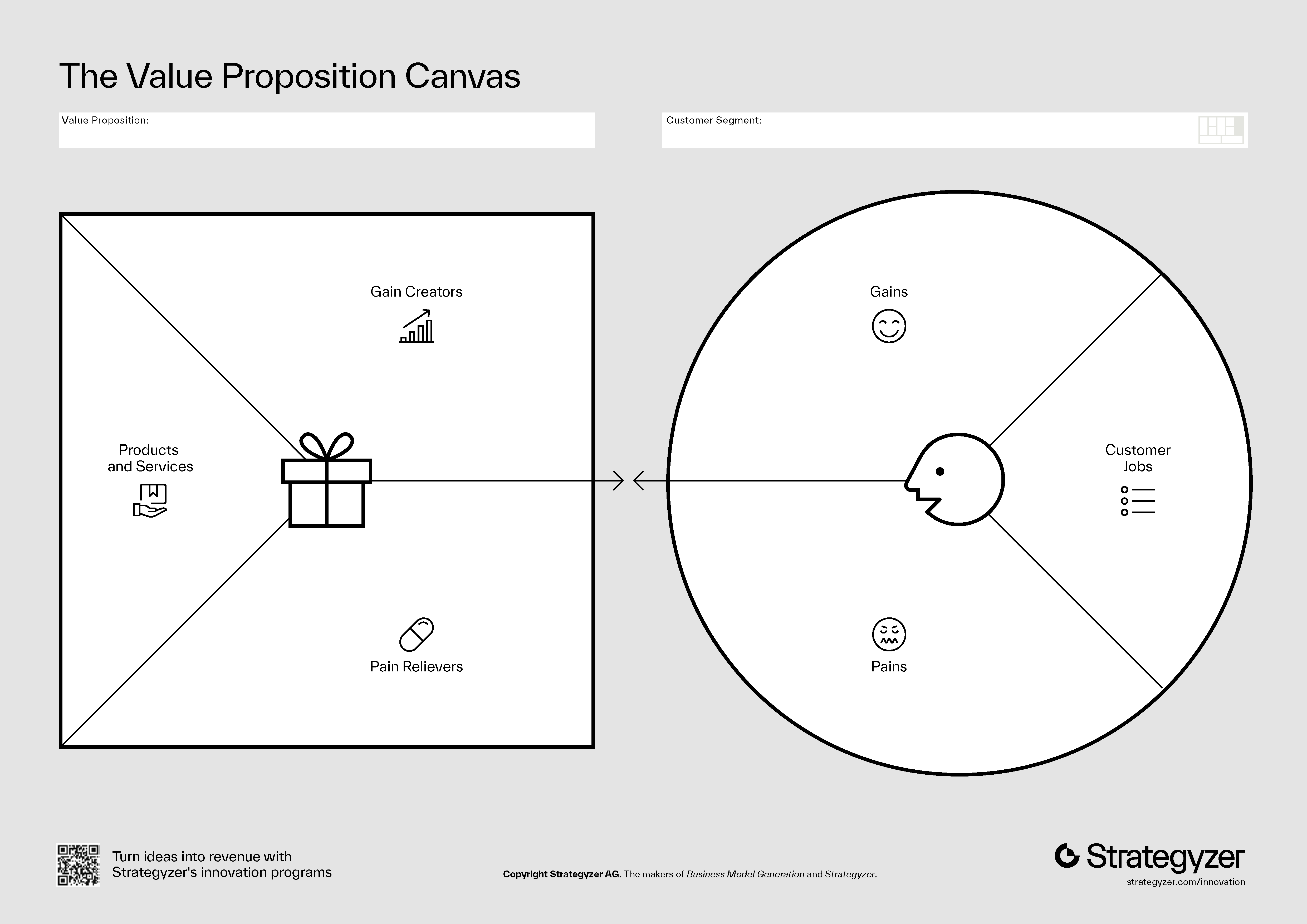

3. Strategyzer’s Value Proposition Canvas (Alexander Osterwalder)

The Value Proposition Canvas, developed by Alex Osterwalder is a practical tool to ensure there is a fit between your product and the market needs. It’s essentially a visual framework that forces you to map out two sides: the Customer Profile (what your customer is trying to do and what they value) and your Value Map (how your product creates value for them). The goal of using the canvas is to iteratively refine your value proposition until what you offer matches what the customer truly wants or needs .

How does it work? The canvas is divided into six components (sometimes depicted as a circle and a square):

- Customer Profile (Right Side): This is where you detail your understanding of the customer.

- Jobs-to-be-Done: What are the tasks, problems, or goals your customer has? (Think back to JTBD – functional jobs, but also social/emotional jobs count here.) What is the customer trying to accomplish or get done?

- Pains: What are the pain points, obstacles, or risks the customer experiences in the context of those jobs? What annoys or frustrates them? What’s costly or inefficient or risky about the current solutions or their current situation?

- Gains: What are the positive outcomes or benefits the customer wants? What would delight them? These can include concrete benefits (e.g. save time, save money) or aspirational gains (status, peace of mind, etc.).

- Value Map (Left Side): This corresponds to your product/service offering.

- Products & Services: List the core products, features, or services you offer that are relevant to the customer’s jobs. (If you have multiple offerings, you might do one canvas per segment/offer.)

- Pain Relievers: How does your product alleviate the pains you listed on the customer side? In what ways do you eliminate or reduce those frustrations, costs, or risks for the customer?

- Gain Creators: How does your product create gains or added value for the customer? In what ways do you provide the benefits or outcomes the customer desires?

The idea is to map each pain to a pain reliever, each gain to a gain creator – and see where you have a strong match and where you might have gaps . When the product’s pain relievers and gain creators align tightly with the customer’s pains and gains, you have a compelling value proposition for that customer segment. If you find mismatches (e.g. you offer gain creators for gains the customer doesn’t care much about, or you leave major pains unaddressed), that signals a need to adjust your product or redefine your segment/UVP.

Using the Value Proposition Canvas can be an eye-opening exercise because it forces specificity. For example, it’s not enough to say “our value prop = save time for users.” The canvas pushes you to articulate: save time doing what, how much time, and by addressing what pain? Perhaps the pain is “entering data manually takes hours each week” and the pain reliever is “auto-import feature cuts data entry to minutes” – that level of detail will strengthen your UVP (“Automated data import that saves hours of manual entry every week” is a clearer, stronger UVP element than generically “we save you time”).

How to use this framework: Take a specific customer segment (ideally one of your early adopter segments) and map out their jobs, pains, gains. Then map your product’s features to pain relievers and gain creators. Once done, step back and craft a value proposition statement that encapsulates the biggest job/pain you solve and the biggest gain you provide.

The Value Proposition Canvas is especially handy if you’re struggling to articulate your UVP because it gives you a structured template. It’s also a great tool to check for completeness – have you really thought about the emotional/social gains? Did you consider all possible pains? Are you mapping features to real benefits or just assuming? By working through it, you ensure your UVP isn’t just a marketing slogan, but a well-founded promise tied to actual customer needs.

Real-World Examples of Effective UVPs (CEE Startups)

Let’s look at some concrete examples of strong value propositions from startups in CEE.

- UiPath (Robotic Process Automation – Romania): “We make software robots, so people don’t have to be robots.” . UiPath used this witty tagline to convey their UVP when they were a fast-growing startup in the RPA space. Why it works: it humanizes a complex automation technology and highlights the benefit. The phrasing puts a playful spin on what could otherwise be dry (“software robots”) and nails the outcome – freeing people from doing tedious, robotic work. It implies who benefits (people stuck doing repetitive tasks), what the solution is (software robots/automation), and the value (you get to stop being a robot at work!). The tagline is also memorable and differentiating – at the time, not many were talking about “software robots” in that catchy way. As a result, it helped position UiPath as an approachable, people-centric automation platform. (It’s worth noting that UiPath’s broader messaging was about “accelerate human achievement”, but this particular UVP tagline drilled down to a relatable pain point and outcome.)

- Pipedrive (Sales CRM – Estonia): “CRM that salespeople love.” Pipedrive entered the crowded CRM (customer relationship management) market, but their UVP zeroed in on a specific differentiation: usability for the sales rep (not just features for management). Why it works: It targets a clear customer group – salespeople – and promises a benefit they care about: a CRM they will actually enjoy using. Traditional CRMs were notorious for being clunky and hated by the sales teams forced to use them. By saying “CRM that salespeople love,” Pipedrive immediately sets itself apart as a tool built for the end user’s delight. It’s simple and outcome-oriented (love = ease of use, helps them sell better). It also implies proof by existence – if salespeople love it, it must be doing something right (in fact, one case study noted that this tagline initially “lured in” users who were frustrated with other tools ).

- Grammarly (Writing assistant – originally from Ukraine): “Great Writing, Simplified.” . Grammarly provides AI-driven writing corrections and suggestions. This short UVP line has been one of their core messages. Why it works: It’s extremely concise – just two words and a comma – yet packed with meaning. It promises the user (anyone who writes) the ultimate outcome they seek: great writing, and it implies the key benefit: made simple. In other words, Grammarly’s value prop is that it makes the complex, painstaking task of writing well much easier. This phrase clearly communicates the problem (writing is hard and time-consuming) and the solution (Grammarly makes it easier) without any fluff . It’s outcome-focused (“great writing” is the end result) and also differentiated – it doesn’t just say “we’re an AI grammar checker” like a feature, it says what the user truly wants (to write something great) and how Grammarly delivers (simplifying the process). This UVP works across multiple customer segments (students, professionals, etc.) because virtually everyone values clear, effective writing, and the pain (it’s hard to do consistently) is ubiquitous. By being so straightforward and universally relevant, Grammarly’s UVP helped it spread widely (people immediately grasp it). The lesson here is the power of simplicity and focusing on the end benefit to the user, not the tech behind it.

Food for thought:each of these UVPs is short, but hints at a larger story. UiPath hints at freeing you from drudgery, Pipedrive hints at a tool built for the rep’s happiness, Grammarly hints at effortless improvement. In your own UVP, aim for that mix of clarity and implied story.)

Now that we’ve broken down what a UVP is, why it’s important, frameworks for thinking about it, and seen some examples, it’s time to craft your own. In the next section, we’ll walk through a step-by-step process to create a compelling value proposition from scratch.

Step-by-Step Guide: Crafting Your UVP

Defining a great UVP is an iterative process that blends research, creativity, and testing. Below is an 7-step process you can follow, from initial customer insights to finally putting your UVP into action.

Overview of the 7 Steps:

- Define Your Customer: who are you targeting?

- Identify their Jobs/Pains/Needs: what do they need to get done and what pain points frustrate them the most?

- Map Current Alternatives: how are those needs currently met (or not) by others?

- Clarify Your Advantage: how can you do it better or differently?

- Add Proof Points: how can you back your UVP up with evidence and specifics?

- Test & Iterate: get feedback, run experiments, and refine the UVP.

- Deploy Consistently: integrate your refined UVP across all customer touchpoints and comms.

Let’s dive into each step in detail:

- Define Your Customer: start by clearly defining who you are trying to deliver value to. You might segment your target customers by demographics (e.g. age, location), by role or industry (e.g. HR at SaaS companies), by behavior (e.g. gamers who live-stream), or by situation (e.g. frequent business travelers). The point is to narrow your focus to a specific group for whom you can craft a tailored UVP. If you have multiple distinct segments, pick one to focus on initially (you can repeat the process for others later).Why is this step critical? Because a UVP that tries to speak to everyone often ends up resonating with no one. For example, suppose your startup is an online language tutoring platform. A broad definition like “anyone who wants to learn a language” is too generic. Instead, you might segment and find that your best early customers are working professionals in non-English-speaking countries who need to improve their English for career advancement. That’s a very specific group with specific needs – which leads us to the next step.

- Identify their Jobs/Pains/Needs: now deeply examine what your chosen customer segment is trying to achieve or what problem they desperately need solved. Use the Jobs-to-Be-Done framework here: figure out the job they “hire” products for. List out: What is the primary goal or task they need help with? What are the current pain points or frustrations they encounter? What outcomes do they value? Sometimes it helps to write a short narrative of a day in the life of your customer or a specific scenario where they’d use your product. Using the above example (professionals improving English), the “job” might be: “I need to practice spoken English so I can present confidently at work and advance in my job.” Pains might include: “Traditional classes don’t fit my schedule,” “I’m embarrassed to speak in front of peers,” “apps feel impersonal and I lose motivation.” Desired gains might be: “a convenient, private way to practice,” “feedback from a friendly tutor,” “noticeable improvement in a short time.” Capture these insights. Be as concrete as possible – the language customers use to describe their problems is valuable raw material for your UVP wording. This step ensures your UVP is rooted in reality. You’re essentially gathering the raw ingredients of your value proposition here: the context and motivation that give your product meaning.

- Map Current Alternatives: next, look outward at the competitive landscape (and alternative solutions) for your target segment. This includes direct competitors (other companies offering similar products) and indirect alternatives (the “DIY” or non-obvious ways people currently solve the problem). Continuing our example: direct competitors might be other online tutoring services; indirect might be “use Duolingo app” or “hire a private tutor locally” or even “do nothing and hope basic English is enough.” Make a simple map or list: for each main need/pain you identified, see how well each alternative addresses it (you can do a grid or just notes). The goal here is to uncover gaps and differentiators. Perhaps you find that none of the existing solutions offer flexible scheduling and one-on-one speaking practice at an affordable price – that gap could be your opening. Also pay attention to how competitors position themselves. What are their UVPs or taglines? Are they all saying the same generic thing? That’s an opportunity for you to stand out with a different message. For example, if all language apps advertise “fun and games to learn languages” but ignore the serious professional user’s need, you might differentiate by focusing squarely on “achieve professional fluency faster” – a more outcome/results-driven pitch. This mapping exercise prevents you from crafting a UVP that’s either me-too (identical to others) or easily outgunned. It forces you to ask: What do we offer that others don’t? or What can we emphasize that’s currently undervalued in the market? Perhaps you have a unique technology, a unique approach, or even a philosophical difference. Write down at least a few bullet points of your potential competitive advantages (or what you intend to be different about your approach). At this stage, also decide if competing on cost is part of your value prop – e.g. “80% cheaper than X” – or if you’re differentiating on quality/experience despite possibly higher cost. All these insights will feed into how you articulate your UVP.

Now it's time to formulate the UVP.

One classic formula (from Geoffrey Moore) is:

For (target customer) who (need or opportunity), (Product name) is a (category/type of product) that (key benefit or solution). Unlike (primary alternative), it (primary differentiator).

Fill in that template for your startup as a starting point. It forces you to be specific. For example: “For working professionals in non-English-speaking countries who need to improve their English speaking skills for career advancement*,* LingoNow is an on-demand tutoring platform that provides one-on-one English practice with native speakers anytime, anywhere*. Unlike* scheduled weekly classes or language apps*, it* offers instant, personalized sessions on your schedule*.”* That’s a mouthful if you read it aloud, but it contains all the critical elements of the UVP. You might not publish that whole paragraph on your website, but it gives you the pieces to work with. Maybe the customer-facing UVP becomes the distilled version of that: “On-demand 1:1 English practice with native tutors, so you can advance your career” – and maybe a subheading: “LingoNow lets you instantly connect with a native English tutor for a speaking session whenever you have 15 minutes to spare. Build confidence on your own schedule.” The point is, start verbose and then trim it down to a polished statement. Ensure the final wording is clear, conversational, and compelling. It should highlight the outcome/benefit, and ideally hint at the differentiator (e.g. “on-demand” vs scheduled, in our example). Avoid superlatives or hype that can’t be proven (like “world’s best” or “revolutionary”) – instead, use concrete descriptors. If possible, also try to inject your brand’s voice or a bit of personality, as long as it doesn’t dilute clarity. For instance, UiPath’s “so people don’t have to be robots” added personality without losing clarity. This is a good time to brainstorm multiple versions and variants. Write 5 different phrasings of your UVP and get opinions. Sometimes an unexpected phrasing resonates more. Pro tip: test it on a stranger – give someone who doesn’t know your business a draft of your UVP and ask them to parrot back what they think it means. If they can’t, it’s not clear enough. Keep refining until a first-time reader would “get it” immediately. By the way: don’t be discouraged – this can take many tweaks! Even pros iterate on phrasing a lot. - Clarify Your Advantage: By now you have three key inputs: customer’s jobs/pains, the current alternatives, and what you do (or will do) differently. Step 4 is about crystallizing your unique angle. Ask yourself, “What is our superpower for this customer?” or “What can we promise that no one else can (or is) promising?”. This often means picking the top 1-3 benefits that matter most and where you excel. For instance, from customer research you might have 10 possible benefits; you cannot emphasize all in one UVP, so prioritize. One approach is to use a simple value matrix: list your key features/capabilities vs. competitor capabilities and mark where you win. But remember, customers buy benefits, not features, so translate those winning features into benefits. Example: your platform uses AI to match students with tutors (feature), and the benefit is “instant matching with the perfect tutor for your needs.” If no one else does that, that’s a unique benefit. Or your benefit might be qualitative, like “the most user-friendly interface” – but be careful, claims like that are vague unless you can tangibly back them up (could be “set up your first lesson in 60 seconds” as a way to demonstrate ease). At this stage, draft a brief statement of your unique value in one or two sentences. Don’t worry about wordsmithing it perfectly yet – focus on the substance. For example: “Unlike traditional tutoring, [OurProduct] offers on-demand 1:1 practice with vetted native speakers, so you can improve your spoken English on your schedule. No scheduling hassles, no awkward group classes – just personalized coaching whenever you need it.” This is a rough value proposition description hitting differentiation (on-demand, 1:1, personalized) and outcome (improve spoken English confidently). You might have a couple of these rough statements if you’re exploring different angles. That’s fine, we’ll refine soon. The key in this step is to articulate your core differentiators in customer-centric terms. Ask, “so what?” for each differentiator to ensure you’re explaining why it matters to the customer. By the end of this process, you should have a clear idea of the main benefit you want to claim and why it's unique.

- Add Proof Points: After you have a UVP statement you’re satisfied with, ask yourself: “How can I prove or show this claim?” This step is about backing up your UVP with evidence, which is very important when talking to skeptical audiences like customers or investors. A strong claim alone may be overlooked, but a claim backed by facts or examples is much more persuasive. There are a few types of proof points:You’ll incorporate these proof points primarily in your detailed messaging (website copy, pitch deck, etc.), but it’s good to have them ready as part of your UVP development. Think of your one-line UVP as the tip of a spear, and these proof points as the shaft that drives it in. When someone says “Oh yeah? Says who?”, you’ll have an answer. In practical terms, for a startup founder, this might mean collecting customer success stories or running a small experiment to get data. For example, you could run a controlled test of users using your product vs. not, to quantify time saved, and then tout “save 3 hours/week on X task.”

- Data/Numbers: If you have any metrics, use them. E.g. “improve your English 2x faster than classes” (if you can support that), or “save $5,000 a year on travel costs,” or “used by 500,000 learners worldwide.” Specific numbers add weight. Even if early-stage, maybe you have a stat from a pilot or a research finding to leverage.

- Testimonials/Quotes: A short quote from a user or an expert can reinforce the UVP. E.g. “I got a promotion thanks to LingoNow – it’s like having a personal coach 24/7,” says [Happy Customer]. Social proof (logos of companies using your product, number of users, etc.) also counts here.

- Demo or Visual Proof: Sometimes showing is proving. If your value is speed, maybe an animation or video snippet of something happening in 30 seconds does the trick. If it’s quality, maybe a before-and-after comparison. Consider if a short phrase or image alongside your UVP can act as proof. For instance, when Revolut started advertising “Transfer money abroad instantly without crazy fees,” they backed it up by showing the actual low fee and exchange rate in an example, proving their claim of low cost.

- Specificity: Even without third-party proof, making your UVP more specific in itself makes it more credible. Saying “on average 5 minutes” is more believable than “super fast,” for instance. So revisit your wording: is there an opportunity to be more concrete? (But only if truthful!)

- Test and Iterate: You’ve got a UVP statement and some backing points – now it’s time to take it to the wild and see how it performs. This step is about getting real-world feedback to refine your UVP. There are a few ways to test:The key is to treat your UVP as a hypothesis and be willing to iterate. Maybe you find out that your target segment actually responds better to a different benefit than you thought – pivot the UVP to that. Or feedback might tell you it’s too wordy – simplify it further. This is normal! Many famous companies tweaked their UVPs over time as they learned. The outcome of this step is a refined UVP that you have confidence in because it’s been test-driven. Keep in mind that iteration is ongoing – even after you officially roll out your UVP, continue to listen to customer feedback and monitor metrics. Markets evolve, and you might need to adjust your value proposition if you target new segments or add new capabilities. But the core should remain consistent as long as it’s working.

- Customer Feedback: Go back to some potential customers (or friendly beta users) and pitch your UVP to them (verbally or in marketing material) without a lot of explanation. Watch their reaction or ask for their interpretation. Do they respond with excitement? Do they understand it? What words or questions do they throw back? You might discover they care about a different aspect than you emphasized, or that a word you used is confusing. Adjust accordingly.

- Landing Page Test: A classic method – create a simple landing page (even if your product isn’t ready) with your UVP as the headline and maybe a sign-up or “learn more” call to action. Drive some traffic to it (via ads or communities) and see if people bite. For instance, run an A/B test: Version A has wording X, Version B has wording Y. Which gets more sign-ups or clicks? This is quantitative evidence of resonance. Even a small-scale test with a few hundred views can provide insights (did 5% sign up or 0.5%? What does that tell you about clarity/appeal?).

- Pitch Testing: If you’re pitching to investors or mentors, gauge where they nod versus where they look confused when you state your UVP. Sometimes a slight tweak (using a more familiar analogy or changing an order of words) can make a big difference in comprehension.

- Social or Ad Experiments: You can also test messaging in social media posts or small ad campaigns. For example, run two Facebook ads with different UVP phrasing (targeting your audience) and see which gets more engagement. This can be quick and illuminating.

- Deploy Consistently: finally, with a validated UVP in hand, ensure it is embedded in everything you do. Consistency is key – your UVP should become a guiding star for both external messaging and internal decision-making. On the external side, integrate your UVP into your website home page, landing pages, pitch decks, marketing materials, and sales scripts. It should be the first thing a visitor sees on your site (often as the main headline or hero text). Use it in one form or another in your social media bios, press releases, etc. Repetition helps it stick in the minds of customers. Also, ensure your branding and design support it – e.g. if your UVP is about simplicity, your UX and website should feel simple, not cluttered. Make sure every team member, from engineering to customer support, can articulate the value proposition in their own words and understands the promise we are making to customers. This helps in decision-making: when scoping features, you can ask “Does this feature reinforce our core value proposition or distract from it?” When planning marketing, you ask “Are we communicating our UVP consistently here?” If everyone is aligned, you won’t have one person advertising one benefit while another focuses on a different message. Some startups even put the UVP on the office wall or in the onboarding documents for new hires. Finally, as you scale, periodically conduct a UVP audit (one of the exercises later) to ensure your communications in all channels still line up. The UVP you crafted is a living part of your strategy – keep it at the forefront and it will continue to guide cohesive growth..

Before wrapping up, let’s get hands-on with some exercises to further sharpen your UVP and avoid common pitfalls.

Hands-On Exercises to Refine Your UVP

To truly internalize these concepts, it helps to roll up your sleeves and practice. Here are five practical exercises you can do (individually or with your team) to craft and polish your value proposition. These exercises are designed to be interactive and insightful – great for workshops or personal brainstorming sessions.

UVP Mad-Libs

Goal: Create structured UVP drafts that capture all essential elements.Fill in the blanks:For [TARGET CUSTOMER] who [NEED OR DESIRE], [PRODUCT/COMPANY] is a [CATEGORY] that [BENEFIT/RESULT]. Unlike [COMPETITOR/ALTERNATIVE], it [UNIQUE DIFFERENTIATOR].Instructions:Refinement process:

- Read each version aloud – where does it feel awkward?

- Merge clauses or simplify language as needed

- Convert the best version into a customer-facing tagline

Example transformation:

- Draft: "For busy parents who want healthy home-cooked meals but lack time, QuickChef is a meal kit service that provides 15-minute gourmet recipes and pre-prepped ingredients. Unlike other meal kits, it requires no chopping and offers kid-friendly options."

- Refined: "QuickChef – Home-cooked gourmet meals in 15 minutes (no chopping required)."

Team alignment tip: Have each team member fill the template independently, then compare results to check alignment and discover different perspectives*.*

- Complete this template for 3–5 different variations

- Try different target segments if you have multiple audiences

- Explore different positioning angles for the same segment

- Don't worry if it sounds clunky initially – focus on capturing all the key elements

Mock Landing Page Test

Goal: Test UVP clarity and appeal through realistic user interactions.Create your mockup:Tools to use:

- Simple: PowerPoint, Keynote, or Google Doc

- Advanced: Wix, Webflow, Lovable or any basic website builder

Testing methods:Option 1 - Direct feedback:

- Show mockup to 5-10 target users or strangers

- Ask: "What do you think this product does?" "Who is this for?" "Does this interest you? Why/why not?"

Option 2 - Live testing:

- Put page online and drive small amount of traffic

- Measure: Click-through rates, email signups, time on page

- A/B test competing UVP versions if you have multiple options

Success indicators:

- ✅ People quickly understand what you do

- ✅ They can identify the target audience

- ✅ They show genuine interest ("tell me more")

- ✅ Clear engagement metrics if testing live

Red flags:

- ⚠️ Confusion about product purpose

- ⚠️ Can't identify who it's for

- ⚠️ Quick bounce or disinterest

- ⚠️ Low engagement rates

Iterate based on feedback: Use insights to refine your headline, supporting points, or overall positioning before building full marketing campaigns.

- Headline: Your UVP statement

- Subheadline: Supporting context (optional)

- 3 key benefit bullets: Drawn from your earlier UVP work

- Call-to-action: "Sign up now," "Learn more," or "Get beta access"

Competitive Positioning Grid

Goal: Identify your unique market position and competitive differentiators.

Step 1 - Create a 2x2 grid

Step 2 - Choose your axes: Select two dimensions that matter most in your market:

Step 3 - Plot competitors:

- Map 5-8 major competitors based on how they perform on both dimensions

- Include established players and direct alternatives

- Be objective about their actual positioning

Step 4 - Add yourself:

- Plot your startup honestly on the same grid

- Look for empty quadrants or underserved positions

Alternative method - Feature comparison table: Create a simple table listing competitors vs. key features/benefits, marking who offers what. Look for empty columns only you can fill.

Analysis questions:

- Do you occupy a quadrant alone?

- What positioning gaps exist?

- Where do competitors cluster?

- What's your clearest differentiator?

Extract your positioning statement: Write 1-2 sentences capturing your unique position

- Example 1: "We are the only budget app built specifically for couples (not individuals)"

- Example 2: "We provide enterprise-level analytics at solo entrepreneur prices – high power, low cost"

- Common options: Price (low/high), Quality (low/high), Target focus (mass/niche), Feature approach (simple/complex)

- Creative options: Traditional/Innovative, Automated/Manual, Broad/Specialized

UVP Audit (Checklist Review)

Goal: evaluate an existing UVP against a checklist of criteria.

Create a list of questions:

- Is it immediately clear what the product/service is or does?

- Is the target customer or context apparent?

- Does it highlight a specific benefit or outcome for the customer?

- Is it differentiating (i.e., could this statement easily apply to many others, or only to us)?

- Does it avoid jargon and fluffy buzzwords?

- Is it short enough to remember and say out loud easily?

- Would it make you interested if you were the target customer?

Reverse-Engineer a Famous UVP

Goal: Decode successful UVPs to improve your own messaging skills and spark positioning ideas.

Choose your target: Pick a well-known company's UVP, tagline, or slogan to analyze.

Detective framework: For each UVP, identify these hidden elements:

🔍 Target customer:

- Who is this clearly speaking to?

- What clues reveal the intended audience?

🔍 Implied need/pain:

- What problem does this suggest they're solving?

- What frustration or desire is being addressed?

🔍 Differentiation strategy:

- What makes this unique or compelling?

- How does it position against competitors?

Analysis examples:

Slack: "A messaging app for teams who put robots on Mars"

- Target: High-performing, techy teams (NASA-level engineering)

- Need: Reliable communication for complex projects

- Differentiator: Social proof + ambition signaling ("good enough for Mars missions")

Domino's: "30 minutes or it's free"

- Target: Hungry customers who value speed

- Need: Fast, hot pizza delivery

- Differentiator: Time guarantee (unprecedented then)

Wise (TransferWise): "Send money abroad for less – up to 8x cheaper than banks"

- Target: International money senders

- Need: Low-cost, easy transfers

- Differentiator: Dramatic savings with specific proof (8x cheaper)

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even with a solid process, there are some classic mistakes that entrepreneurs make when defining their value propositions. Here are a few common pitfalls to watch out for, along with tips on how to avoid or fix them:

- Using Jargon and Buzzwords - avoid impressive-sounding but irrelevant terms. Instead use language a 12-year-old would understand.

- Being Vague or Generic - avoid sounding nice but saying nothing specific. Get specific about who, what problem, and how. Always err on the side of concrete language: e.g. number of minutes saved, specific domain (“for marketers” vs “for professionals”), specific outcome (“double your email response rate” vs “improve marketing”). Specificity not only differentiates you, it makes your promise credible.

- Lacking Differentiation (Sounding Me-Too): your UVP might be clear and even specific, but if it’s essentially the same claim everyone else makes, it won’t stick. Highlight what only you offer. A trick: explicitly include a phrase like “only” or “unlike others, we ___” in your internal drafts. Even if you remove those words later, it forces you to fill in the blank of what only you offer.

- Being Too Feature-Focused (Not Benefit-Focused): features are just a means to an end. Customers want to know "what's in it for them?" Tie every feature to a customer benefit.

- Trying to Squeeze in Too Much: A UVP should be punchy and focused. If you have multiple major benefits, you can mention one or two in the headline and perhaps list others in a sub-bullet format. But if you list everything, nothing stands out. Lead with the strongest benefit, mention others separately.

- Being Internally Misaligned: you have a polished UVP statement, but then your other messaging or product don't align (e.g. you claim to be the "simplest tool on the market" but your website is cluttered and your product is hard to use. To avoid this, ensure all customer touchpoints echo your UVP.

Bottom line: Draft first, then edit ruthlessly. Remove fluff, ambiguity, and me-too language until you have a razor-sharp statement that cuts through to your audience.

Every successful startup needs a Unique Value Proposition (UVP) at its core. A UVP is more than a catchy tagline – it’s the fundamental promise of value that you deliver to customers, and it underpins your entire business strategy. A strong UVP guides what you build, how you talk about your product, how you position against competitors, and even how you pitch to investors. In early stages, founders often wear many hats, but one of the most critical tasks is articulating exactly why your product is different and worth paying attention to.

Why focus on UVP?

A well-defined UVP becomes a strategic tool that influences everything: product decisions, messaging and branding, market positioning, fundraising narratives, and internal alignment. Like the unseen foundation of a house, a strong UVP supports everything built on top of it. It clarifies your vision and rallies your team around a common purpose. On the flip side, an unclear or generic value proposition can confuse customers and even raise red flags with investors (a vague, buzzword-filled tagline often signals a lack of clarity in vision). By investing time upfront to nail your UVP, you establish a “north star” for your startup’s growth.

What is a Value Proposition?

In simple terms, a value proposition is a concise statement of the unique benefit your product or service delivers to a specific customer segment. It’s the answer to the customer’s eternal question: “Why should I choose your solution over all the others?” A good UVP is typically a single, clear, and compelling message that communicates:

- what you offer,

- who is it for, and

- why it's better or different than alternatives.

Why does a UVP matter so much?

- Customer Appeal: a well-crafted UVP makes it immediately obvious what problem you solve and why it’s relevant to them. It improves your conversion, retention, and referrals.

- Consistent Branding and Messaging: it keeps your marketing copy, sales pitches, and even investor decks on-message and aligned.

- Internal Alignment: for everything from product development to marketing. Every feature you build and every campaign you launch should ladder up to the value promised in your UVP.

- Investor Confidence: VCs often make snap judgments based on how clearly you can state the problem you solve and the benefit you provide.

What Makes a Good UVP?

Not all value propositions are created equal. Some are unforgettable and compelling, while others fall flat. Here are a few hallmarks of a strong UVP:

- Clear & Simple: It’s straightforward to grasp instantly, even for someone without expertise. Steer clear of jargon and buzzwords; opt for simple, direct language instead. An effective UVP should not leave people confused – it should "click" right away.

- Customer-Centric & Outcome-Focused: A great UVP speaks to the outcome or benefit the customer cares about – not just a list of features. It addresses a concrete problem, need, or desire. In other words, it’s about them, not you. For example, instead of “We use advanced AI algorithms,” an outcome-focused UVP would be “We help you find fraud 5x faster using AI.” Focus on how you improve the customer’s life or business. The product or feature is not the value - it’s how value is delivered.

- Unique & Differentiated: Your value proposition should highlight what sets you apart. If it could just as easily describe your competitor, it’s not unique enough. A good UVP might explicitly or implicitly answer “Why us and not the other guys?” – whether that’s a unique approach, an exclusive resource, superior performance, cost advantage, etc. For instance, “the only budget app built specifically for freelancers” is inherently differentiated. Often, the specificity of your target or outcome can make it unique (e.g. “for busy moms,” “for B2B SaaS marketers,” “save 10 hours/week,” etc.). Don’t be afraid to niche down – a focused UVP for a specific audience is usually stronger than a vague one trying to please everyone.

- Credible & Testable: A strong UVP is one you can back up with evidence – and one you can validate through testing. It’s essentially a hypothesis about what customers value, so it should be framed in a way you can test and refine. For example, if your UVP is “Cut online checkout time in half,” you can measure whether users indeed checkout faster with your product. Being specific (with metrics or concrete claims) not only makes your UVP more credible, but it also gives you something to prove. You’ll want to incorporate proof points – facts, data, or testimonials that support your claims . For instance, if you claim “fastest delivery,” you should have data like “delivered in under 2 hours on average” or a customer quote to back it up. Moreover, treat your UVP as a living hypothesis: put it in front of customers (on a landing page, in a pitch, etc.) and see if it resonates, then iterate.

- Concise & Memorable: The best UVPs don’t try to cram in every detail. They often consist of a tagline or sentence plus maybe a short supporting sub-header or bullets. The idea is to communicate one big thing that sticks. Think of slogans or one-liners that have stuck with you (Just Do It – Nike or Be less busy - Slack).

Next, we’ll dive into some frameworks that can help you formulate your UVP, and then we’ll see real examples and go through a step-by-step process to create your own.

Three Frameworks to Define Your UVP

There is no one-size-fits-all formula for a value proposition, but there are proven frameworks that can guide your thinking. Here we introduce three influential frameworks to help you clarify your UVP from different angles: Jobs to Be Done, Porter’s Value Proposition Triangle, and Strategyzer’s Value Proposition Canvas. Each framework offers a lens for understanding how your product creates value in a unique way.

1. Jobs to Be Done (Clayton Christensen)

Why do customers really buy your product? The Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) framework, popularized by Clay Christensen, helps you answer this by shifting perspective: instead of focusing on customer demographics or product features, look at the underlying “job” the customer is hiring your product to do. In Christensen’s words, "customers don’t simply buy products; they “hire” them to get a job done" . Every purchase has a context and motivation behind it – a problem to solve, a goal to achieve, or a pain to alleviate. JTBD asks: What is the progress the customer is trying to make in their life or business?

Under this framework, you delve into the functional, social, and emotional dimensions of customer needs . For example, the famous “milkshake” example from Christensen’s research showed that people were “hiring” milkshakes in the morning not just for taste, but to relieve boredom on a commute and to have a convenient, tidy breakfast. This insight led to a better product and marketing strategy for milkshakes (e.g. making them thicker so they last longer during a drive, and marketing the morning use-case).

Food for thought:The JTBD mindset would have you fill in the sentence: “When _____ (situation), customers want to _____ (job to be done) so they can _____ (desired outcome).”

How JTBD informs your UVP: Once you identify the core job (or jobs) your product does for the customer, you can craft your UVP around that. It ensures your proposition is outcome-focused (the outcome being the job accomplished) and customer-centric (rooted in the customer’s context). For example, a ride-hailing service’s job-to-be-done might be “get me from A to B quickly and safely.” A UVP for an early ride-hailing startup might then be “Tap a button, get a ride in minutes – the fastest way to get from A to B in the city.” Notice how that speaks to the job (quick, convenient transport) rather than the technology (it doesn’t say “we have an app-based taxi network,” which is feature-focused).

As you develop your UVP, use JTBD to interview customers or observe behavior: ask questions like “What problem were you trying to solve when you used our product?” or “Think of the last time you [context], what did you do and why?” The answers will be gold for phrasing your value in terms that matter to customers (often, you’ll even pick up the exact words customers use – which you can mirror in your messaging).

Key takeaway from JTBD: Frame your value proposition around the job the customer needs done and the outcome they’re seeking, not just around your product’s specs. This ensures your UVP hits the nail on the head in terms of relevance and clarity.

Food for thought:

Customers “hire” products/services to accomplish a “job.”

Your Mission: Identify the job they need done, the pains they face doing it, and the gains or outcomes they aspire to.

Example: A mother “hires” a meal kit delivery service so she can quickly prepare healthy dinners while juggling a busy schedule. She’s not buying “food” but a time-saving, stress-reducing solution.

2. Porter’s Value Proposition Triangle (Michael Porter)

Michael Porter, a renowned strategy professor, describes strategy as defining a unique position, and at the heart of a company’s strategy is its value proposition. Porter suggests that a unique value proposition can be identified by answering three fundamental questions (often depicted as the three points of a triangle):

Porter’s “triangle” model of UVP: strategy is defined by which customers you target, which needs you meet, and at what relative price (or cost).

- Which customers are you going to serve?Within any market, you can segment customers in various ways (by demographics, behavior, size, etc.). A value proposition can be tailored to specific segment(s). Defining who you are focusing on is the first leg of the triangle. For some companies, this is the primary decision: e.g. “We are building for first-time parents,” or “our solution is for freelance graphic designers.” By choosing a distinct target, you automatically shape the other aspects of your strategy. Porter notes that in some strategies, choosing the customer segment comes first, and it guides the needs you will address and the price position you’ll take .

- Which needs (customer problems) are you going to meet? – The second leg is clarifying what key problem, need, or job (to echo JTBD) you will satisfy for the chosen customers. In some strategies, this is the primary focus: you identify an unmet need or a set of needs in the market and build a superior way to meet them. For example, a company might decide, “We will meet the need for affordable on-demand transportation in rural areas” or “We will solve the pain of manual data entry for accountants.” Often, this choice is linked to unique capabilities you have to solve that need. If your UVP is need-driven, it should articulate that unique solution to that pressing customer need.

- What relative price will you offer (and thus, what value/cost trade-off)? – The third leg of Porter’s triangle is your price positioning relative to the alternatives. Are you a high-price, premium value offering? Or a low-cost, “good enough” offering? Some of the most successful value propositions win by changing the price equation. For example, a company may target customers who are overserved and overpaying for existing solutions, and offer a simpler product at a much lower price – capturing those customers with a “good enough” solution at a bargain . Conversely, another company might target customers who are underserved by cheap solutions and are willing to pay more for a premium product that fully meets their needs. Either way, relative price is part of your value proposition: it tells the customer whether you’re a luxury choice, a cost-effective alternative, or mid-range. Importantly, your price must align with the value you deliver and the segment you target (e.g. a cash-strapped small business segment will need a different price/value combo than enterprise clients).

According to Porter, a truly unique value proposition comes from making distinctive choices in these three areas and aligning them. Your UVP essentially boils down to “We serve X customers, fulfilling Y needs, at Z price point (relative to others)”. For example, Ikea’s value proposition can be described via this triangle: Target (X) – cost-conscious young furniture buyers; Needs (Y) – stylish, space-efficient furniture solutions that can be taken home immediately; Relative Price (Z) – significantly lower cost than traditional furniture stores (achieved via flat-pack self-assembly and warehouse stores). All of Ikea’s messaging and strategic decisions align to that UVP (e.g. “Affordable design for the many” is a phrase that captures it).

How to use this framework: Ensure your UVP clearly reflects a choice in who and what – and consider mentioning the element of how/price if it’s a key part of your differentiation. For instance, if your offer is 30% cheaper than competitors for a comparable service, that cost advantage might be front-and-center in your UVP. On the other hand, if you’re premium, your UVP might focus on the superior quality/outcomes and implicitly justify the higher price. The triangle reminds us that being all things to all customers is not a strategy. A strong UVP stakes out a focused position.

Food for thought:

1. Which customers are you going to serve?

2. Which needs are you going to meet?

3. What relative price or quality level?

3. Strategyzer’s Value Proposition Canvas (Alexander Osterwalder)

The Value Proposition Canvas, developed by Alex Osterwalder is a practical tool to ensure there is a fit between your product and the market needs. It’s essentially a visual framework that forces you to map out two sides: the Customer Profile (what your customer is trying to do and what they value) and your Value Map (how your product creates value for them). The goal of using the canvas is to iteratively refine your value proposition until what you offer matches what the customer truly wants or needs .

How does it work? The canvas is divided into six components (sometimes depicted as a circle and a square):

- Customer Profile (Right Side): This is where you detail your understanding of the customer.

- Jobs-to-be-Done: What are the tasks, problems, or goals your customer has? (Think back to JTBD – functional jobs, but also social/emotional jobs count here.) What is the customer trying to accomplish or get done?

- Pains: What are the pain points, obstacles, or risks the customer experiences in the context of those jobs? What annoys or frustrates them? What’s costly or inefficient or risky about the current solutions or their current situation?

- Gains: What are the positive outcomes or benefits the customer wants? What would delight them? These can include concrete benefits (e.g. save time, save money) or aspirational gains (status, peace of mind, etc.).

- Value Map (Left Side): This corresponds to your product/service offering.

- Products & Services: List the core products, features, or services you offer that are relevant to the customer’s jobs. (If you have multiple offerings, you might do one canvas per segment/offer.)

- Pain Relievers: How does your product alleviate the pains you listed on the customer side? In what ways do you eliminate or reduce those frustrations, costs, or risks for the customer?

- Gain Creators: How does your product create gains or added value for the customer? In what ways do you provide the benefits or outcomes the customer desires?

The idea is to map each pain to a pain reliever, each gain to a gain creator – and see where you have a strong match and where you might have gaps . When the product’s pain relievers and gain creators align tightly with the customer’s pains and gains, you have a compelling value proposition for that customer segment. If you find mismatches (e.g. you offer gain creators for gains the customer doesn’t care much about, or you leave major pains unaddressed), that signals a need to adjust your product or redefine your segment/UVP.

Using the Value Proposition Canvas can be an eye-opening exercise because it forces specificity. For example, it’s not enough to say “our value prop = save time for users.” The canvas pushes you to articulate: save time doing what, how much time, and by addressing what pain? Perhaps the pain is “entering data manually takes hours each week” and the pain reliever is “auto-import feature cuts data entry to minutes” – that level of detail will strengthen your UVP (“Automated data import that saves hours of manual entry every week” is a clearer, stronger UVP element than generically “we save you time”).

How to use this framework: Take a specific customer segment (ideally one of your early adopter segments) and map out their jobs, pains, gains. Then map your product’s features to pain relievers and gain creators. Once done, step back and craft a value proposition statement that encapsulates the biggest job/pain you solve and the biggest gain you provide.

The Value Proposition Canvas is especially handy if you’re struggling to articulate your UVP because it gives you a structured template. It’s also a great tool to check for completeness – have you really thought about the emotional/social gains? Did you consider all possible pains? Are you mapping features to real benefits or just assuming? By working through it, you ensure your UVP isn’t just a marketing slogan, but a well-founded promise tied to actual customer needs.

Real-World Examples of Effective UVPs (CEE Startups)

Let’s look at some concrete examples of strong value propositions from startups in CEE.

- UiPath (Robotic Process Automation – Romania): “We make software robots, so people don’t have to be robots.” . UiPath used this witty tagline to convey their UVP when they were a fast-growing startup in the RPA space. Why it works: it humanizes a complex automation technology and highlights the benefit. The phrasing puts a playful spin on what could otherwise be dry (“software robots”) and nails the outcome – freeing people from doing tedious, robotic work. It implies who benefits (people stuck doing repetitive tasks), what the solution is (software robots/automation), and the value (you get to stop being a robot at work!). The tagline is also memorable and differentiating – at the time, not many were talking about “software robots” in that catchy way. As a result, it helped position UiPath as an approachable, people-centric automation platform. (It’s worth noting that UiPath’s broader messaging was about “accelerate human achievement”, but this particular UVP tagline drilled down to a relatable pain point and outcome.)

- Pipedrive (Sales CRM – Estonia): “CRM that salespeople love.” Pipedrive entered the crowded CRM (customer relationship management) market, but their UVP zeroed in on a specific differentiation: usability for the sales rep (not just features for management). Why it works: It targets a clear customer group – salespeople – and promises a benefit they care about: a CRM they will actually enjoy using. Traditional CRMs were notorious for being clunky and hated by the sales teams forced to use them. By saying “CRM that salespeople love,” Pipedrive immediately sets itself apart as a tool built for the end user’s delight. It’s simple and outcome-oriented (love = ease of use, helps them sell better). It also implies proof by existence – if salespeople love it, it must be doing something right (in fact, one case study noted that this tagline initially “lured in” users who were frustrated with other tools ).

- Grammarly (Writing assistant – originally from Ukraine): “Great Writing, Simplified.” . Grammarly provides AI-driven writing corrections and suggestions. This short UVP line has been one of their core messages. Why it works: It’s extremely concise – just two words and a comma – yet packed with meaning. It promises the user (anyone who writes) the ultimate outcome they seek: great writing, and it implies the key benefit: made simple. In other words, Grammarly’s value prop is that it makes the complex, painstaking task of writing well much easier. This phrase clearly communicates the problem (writing is hard and time-consuming) and the solution (Grammarly makes it easier) without any fluff . It’s outcome-focused (“great writing” is the end result) and also differentiated – it doesn’t just say “we’re an AI grammar checker” like a feature, it says what the user truly wants (to write something great) and how Grammarly delivers (simplifying the process). This UVP works across multiple customer segments (students, professionals, etc.) because virtually everyone values clear, effective writing, and the pain (it’s hard to do consistently) is ubiquitous. By being so straightforward and universally relevant, Grammarly’s UVP helped it spread widely (people immediately grasp it). The lesson here is the power of simplicity and focusing on the end benefit to the user, not the tech behind it.

Food for thought:each of these UVPs is short, but hints at a larger story. UiPath hints at freeing you from drudgery, Pipedrive hints at a tool built for the rep’s happiness, Grammarly hints at effortless improvement. In your own UVP, aim for that mix of clarity and implied story.)

Now that we’ve broken down what a UVP is, why it’s important, frameworks for thinking about it, and seen some examples, it’s time to craft your own. In the next section, we’ll walk through a step-by-step process to create a compelling value proposition from scratch.

Step-by-Step Guide: Crafting Your UVP

Defining a great UVP is an iterative process that blends research, creativity, and testing. Below is an 7-step process you can follow, from initial customer insights to finally putting your UVP into action.

Overview of the 7 Steps:

- Define Your Customer: who are you targeting?

- Identify their Jobs/Pains/Needs: what do they need to get done and what pain points frustrate them the most?

- Map Current Alternatives: how are those needs currently met (or not) by others?

- Clarify Your Advantage: how can you do it better or differently?

- Add Proof Points: how can you back your UVP up with evidence and specifics?

- Test & Iterate: get feedback, run experiments, and refine the UVP.

- Deploy Consistently: integrate your refined UVP across all customer touchpoints and comms.

Let’s dive into each step in detail:

- Define Your Customer: start by clearly defining who you are trying to deliver value to. You might segment your target customers by demographics (e.g. age, location), by role or industry (e.g. HR at SaaS companies), by behavior (e.g. gamers who live-stream), or by situation (e.g. frequent business travelers). The point is to narrow your focus to a specific group for whom you can craft a tailored UVP. If you have multiple distinct segments, pick one to focus on initially (you can repeat the process for others later).Why is this step critical? Because a UVP that tries to speak to everyone often ends up resonating with no one. For example, suppose your startup is an online language tutoring platform. A broad definition like “anyone who wants to learn a language” is too generic. Instead, you might segment and find that your best early customers are working professionals in non-English-speaking countries who need to improve their English for career advancement. That’s a very specific group with specific needs – which leads us to the next step.

- Identify their Jobs/Pains/Needs: now deeply examine what your chosen customer segment is trying to achieve or what problem they desperately need solved. Use the Jobs-to-Be-Done framework here: figure out the job they “hire” products for. List out: What is the primary goal or task they need help with? What are the current pain points or frustrations they encounter? What outcomes do they value? Sometimes it helps to write a short narrative of a day in the life of your customer or a specific scenario where they’d use your product. Using the above example (professionals improving English), the “job” might be: “I need to practice spoken English so I can present confidently at work and advance in my job.” Pains might include: “Traditional classes don’t fit my schedule,” “I’m embarrassed to speak in front of peers,” “apps feel impersonal and I lose motivation.” Desired gains might be: “a convenient, private way to practice,” “feedback from a friendly tutor,” “noticeable improvement in a short time.” Capture these insights. Be as concrete as possible – the language customers use to describe their problems is valuable raw material for your UVP wording. This step ensures your UVP is rooted in reality. You’re essentially gathering the raw ingredients of your value proposition here: the context and motivation that give your product meaning.

- Map Current Alternatives: next, look outward at the competitive landscape (and alternative solutions) for your target segment. This includes direct competitors (other companies offering similar products) and indirect alternatives (the “DIY” or non-obvious ways people currently solve the problem). Continuing our example: direct competitors might be other online tutoring services; indirect might be “use Duolingo app” or “hire a private tutor locally” or even “do nothing and hope basic English is enough.” Make a simple map or list: for each main need/pain you identified, see how well each alternative addresses it (you can do a grid or just notes). The goal here is to uncover gaps and differentiators. Perhaps you find that none of the existing solutions offer flexible scheduling and one-on-one speaking practice at an affordable price – that gap could be your opening. Also pay attention to how competitors position themselves. What are their UVPs or taglines? Are they all saying the same generic thing? That’s an opportunity for you to stand out with a different message. For example, if all language apps advertise “fun and games to learn languages” but ignore the serious professional user’s need, you might differentiate by focusing squarely on “achieve professional fluency faster” – a more outcome/results-driven pitch. This mapping exercise prevents you from crafting a UVP that’s either me-too (identical to others) or easily outgunned. It forces you to ask: What do we offer that others don’t? or What can we emphasize that’s currently undervalued in the market? Perhaps you have a unique technology, a unique approach, or even a philosophical difference. Write down at least a few bullet points of your potential competitive advantages (or what you intend to be different about your approach). At this stage, also decide if competing on cost is part of your value prop – e.g. “80% cheaper than X” – or if you’re differentiating on quality/experience despite possibly higher cost. All these insights will feed into how you articulate your UVP.

Now it's time to formulate the UVP.

One classic formula (from Geoffrey Moore) is:

For (target customer) who (need or opportunity), (Product name) is a (category/type of product) that (key benefit or solution). Unlike (primary alternative), it (primary differentiator).

Fill in that template for your startup as a starting point. It forces you to be specific. For example: “For working professionals in non-English-speaking countries who need to improve their English speaking skills for career advancement*,* LingoNow is an on-demand tutoring platform that provides one-on-one English practice with native speakers anytime, anywhere*. Unlike* scheduled weekly classes or language apps*, it* offers instant, personalized sessions on your schedule*.”* That’s a mouthful if you read it aloud, but it contains all the critical elements of the UVP. You might not publish that whole paragraph on your website, but it gives you the pieces to work with. Maybe the customer-facing UVP becomes the distilled version of that: “On-demand 1:1 English practice with native tutors, so you can advance your career” – and maybe a subheading: “LingoNow lets you instantly connect with a native English tutor for a speaking session whenever you have 15 minutes to spare. Build confidence on your own schedule.” The point is, start verbose and then trim it down to a polished statement. Ensure the final wording is clear, conversational, and compelling. It should highlight the outcome/benefit, and ideally hint at the differentiator (e.g. “on-demand” vs scheduled, in our example). Avoid superlatives or hype that can’t be proven (like “world’s best” or “revolutionary”) – instead, use concrete descriptors. If possible, also try to inject your brand’s voice or a bit of personality, as long as it doesn’t dilute clarity. For instance, UiPath’s “so people don’t have to be robots” added personality without losing clarity. This is a good time to brainstorm multiple versions and variants. Write 5 different phrasings of your UVP and get opinions. Sometimes an unexpected phrasing resonates more. Pro tip: test it on a stranger – give someone who doesn’t know your business a draft of your UVP and ask them to parrot back what they think it means. If they can’t, it’s not clear enough. Keep refining until a first-time reader would “get it” immediately. By the way: don’t be discouraged – this can take many tweaks! Even pros iterate on phrasing a lot. - Clarify Your Advantage: By now you have three key inputs: customer’s jobs/pains, the current alternatives, and what you do (or will do) differently. Step 4 is about crystallizing your unique angle. Ask yourself, “What is our superpower for this customer?” or “What can we promise that no one else can (or is) promising?”. This often means picking the top 1-3 benefits that matter most and where you excel. For instance, from customer research you might have 10 possible benefits; you cannot emphasize all in one UVP, so prioritize. One approach is to use a simple value matrix: list your key features/capabilities vs. competitor capabilities and mark where you win. But remember, customers buy benefits, not features, so translate those winning features into benefits. Example: your platform uses AI to match students with tutors (feature), and the benefit is “instant matching with the perfect tutor for your needs.” If no one else does that, that’s a unique benefit. Or your benefit might be qualitative, like “the most user-friendly interface” – but be careful, claims like that are vague unless you can tangibly back them up (could be “set up your first lesson in 60 seconds” as a way to demonstrate ease). At this stage, draft a brief statement of your unique value in one or two sentences. Don’t worry about wordsmithing it perfectly yet – focus on the substance. For example: “Unlike traditional tutoring, [OurProduct] offers on-demand 1:1 practice with vetted native speakers, so you can improve your spoken English on your schedule. No scheduling hassles, no awkward group classes – just personalized coaching whenever you need it.” This is a rough value proposition description hitting differentiation (on-demand, 1:1, personalized) and outcome (improve spoken English confidently). You might have a couple of these rough statements if you’re exploring different angles. That’s fine, we’ll refine soon. The key in this step is to articulate your core differentiators in customer-centric terms. Ask, “so what?” for each differentiator to ensure you’re explaining why it matters to the customer. By the end of this process, you should have a clear idea of the main benefit you want to claim and why it's unique.